Introduction

Most of the time, when you read an article on bootloader and security, there are chances that it will talk about exploiting a vulnerability to unlock a bootloader. This article takes a different path and explains how to lock Samsung's proprietary bootloader (aboot) and to disable the download mode.

In France, and certainly in many countries, Samsung sells smartphones with an unlocked bootloader. That's cool, you can easily root your device. Unfortunately, this also means that anyone can take your phone and flash it in order to infect your phone or to grab your data. To the best of our knowledge, there is no public way to lock your bootloader and to prevent that attack scenario from happening.

Fortunately for us, Samsung left an "undocumented" mechanism in their devices to lock the download mode and to prevent a third party from flashing anything through ODIN. This article is based on Samsung Galaxy S5, but it should works on many others Samsung devices.

Samsung aboot bootloader

When you power on a smartphone, several bootloaders are executed consecutively. Most of the time, you have a PBL (Primary Boot Loader) which is stored in ROM that is executed the first. It loads and executes a SBL (Secondary Boot Loader) which is stored in Flash. PBL and SBL are bootloaders provided by the SoC manufacturer and you can't modify them because they are stored in ROM or they are signed. To allow an OEM to have his own bootloader, the SBL loads and executes the OEM bootloader if its signature is verified. For Samsung devices, the OEM bootloader is aboot.

What is interesting for us is that aboot is based on an open-source bootloader called LK (Little Kernel). This helped a lot during reverse engineering, because one can recover symbols using strings leftover, or by recompilating the LK bootloader and diffing with aboot. But first, let's get our hand on aboot binary.

The aboot bootloader can be easily extracted from a Samsung ROM:

$ tar tvf G900FXXU1BNL9_G900FOXX1BNL3_G900FXXU1BNL9_HOME.tar.md5

-rw-rw-r-- dpi/dpi 986200 2014-12-18 11:09 aboot.mbn

-rw-rw-r-- dpi/dpi 7590656 2014-12-18 11:09 NON-HLOS.bin

-rw-rw-r-- dpi/dpi 228488 2014-12-18 11:08 rpm.mbn

-rw-rw-r-- dpi/dpi 317572 2014-12-18 11:08 sbl1.mbn

-rw-rw-r-- dpi/dpi 361476 2014-12-18 11:08 tz.mbn

-rw-rw-r-- dpi/dpi 12343568 2014-12-18 11:09 boot.img

-rw-rw-r-- dpi/dpi 12747024 2014-12-18 11:09 recovery.img

-rw-r--r-- dpi/dpi 2373600960 2014-12-18 11:10 system.img.ext4

-rw-r--r-- dpi/dpi 54855424 2014-12-18 07:25 modem.bin

-rw-r--r-- dpi/dpi 50708700 2014-12-24 04:23 cache.img.ext4

-rw-r--r-- dpi/dpi 7270584 2014-12-24 04:23 hidden.img.ext4

$ tar xvf G900FXXU1BNL9_G900FOXX1BNL3_G900FXXU1BNL9_HOME.tar.md5 aboot.mbn

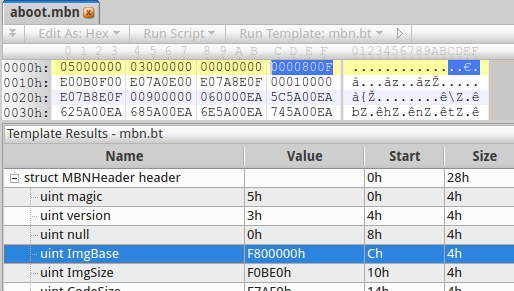

We get a MBN file, which is simply an ARM executable code prefixed with a 40 bytes (0x28) header. In this header, we can find the ImgBase of aboot which will be used in IDA Pro to rebase the binary:

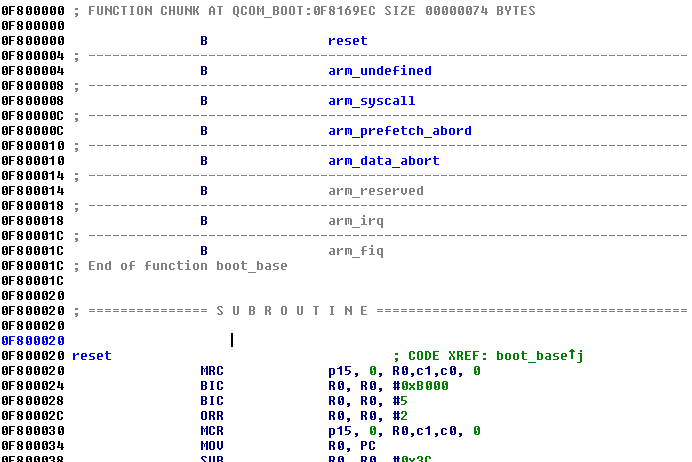

The first thing we see in the bootloader's executable code is the Exception Vector Table:

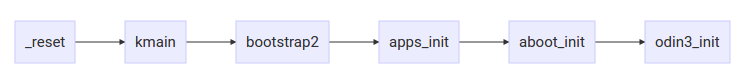

From _reset to aboot_init() functions, we have classical LK flow of execution. Functions called until aboot_init() are mostly executed for hardware/memory initialization purpose.

There are no symbols in the aboot.mbn file. However, it's based on the opensource LK bootloader. Thus, it's pretty easy most of the time to recover symbols, especially when dprintf() debug logs are left in the binary.

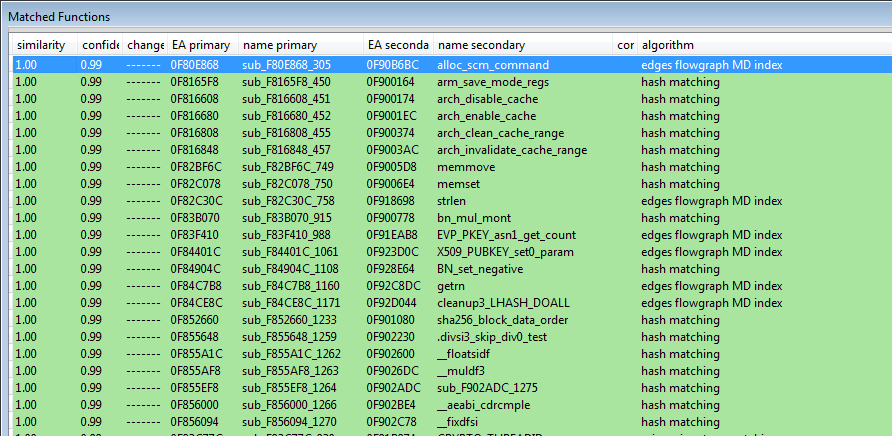

More symbols can also be identified by compiling LK from qualcomm msm8974 SoC and by using bindiff (Pro-tip: Bindiff's algorithm "string references" can give interesting results.):

$ git clone https://android.googlesource.com/kernel/lk -b qcom-dima-8x74-fixes

$ cd lk

$ export TOOLCHAIN_PREFIX=arm-linux-gnueabi

$ make msm8974

$ ls build-msm8974

app arch config.h dev emmc_appsboot.mbn emmc_appsboot.raw EMMCBOOT.MBN kernel lib lk lk.bin lk.debug.lst lk.lst lk.size lk.sym mkheader platform system-onesegment.ld target

$ file build-msm8974/lk

lk: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, ARM, EABI5 version 1 (SYSV), statically linked, not stripped

Let's get back on the topic. We are in the aboot_init function.

Traditionally, this function is used to choose in which mode the device should boot. According to pressed hardware keys (if the user presses VOLUME_UP for example) or the boot reason, it can start fastboot, boot in recovery or boot Android from the flash.

In Samsung's case, it can additionally load the download mode when the user press VOLUME_DOWN and HOME keys.

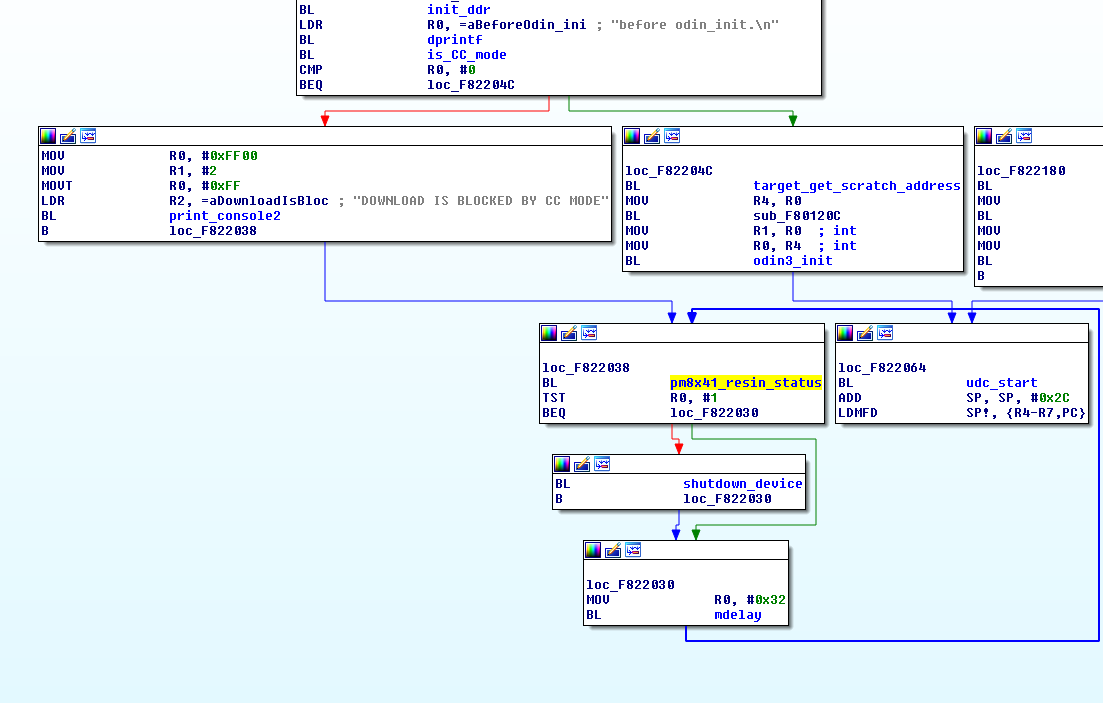

A few instructions before the launch of ODIN through a call to odin3_init(), something catches our eyes:

CC mode and the param partition

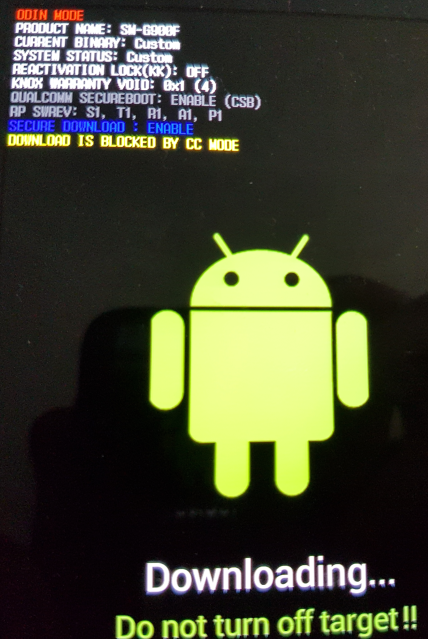

Based on the CFG in the previous screenshot, we note that the bootloader

will either execute odin3_init() or display the message "DOWNLOAD IS BLOCKED BY CC MODE" on screen

depending on is_CC_mode() return value.

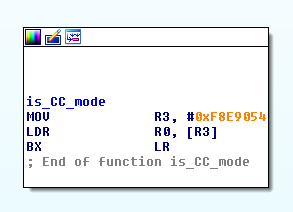

When disassembled, is_CC_mode() has the following instructions:

It returns the DWORD located at 0xF8E9054. Xrefs for this address indicates

that only one function writes at this location. Let's rename this function to init_cc_flag_value().

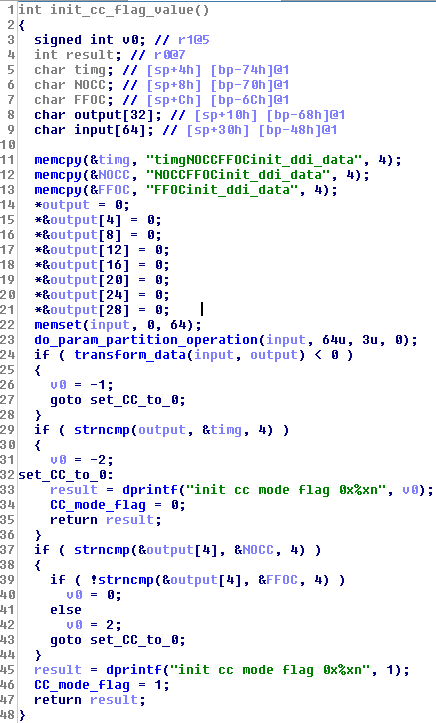

From a high level point of view, a 64 bytes buffer is read via the function renamed do_param_partition_operation(), transformed

into another smaller buffer (32 bytes) via the function renamed to tranform_data() and finally, some comparisons are done on this buffer to check

if the CC flag should be set to 1 or 0. It's important to note that the init_cc_flag_value() is called by the aboot_init() function in

aboot_check_mode().

Let's go a bit deeper by analyzing the functions do_param_partition_operation() and transform_data().

The function do_param_partition_operation() is used to read or write data into a partition named "param". The reconstructed function header can be:

int do_param_partition_operation(char *buffer, unsigned int size, unsigned int type, unsigned int operation);

The param partition is used to store different types of data that are Samsung-specific. The type parameter

is used to calculate the offset at which the operation will be done. The operation parameter is used to specify if we want to read (0) or

write (1) data. And finally buffer and size are used to specify the address of the buffer to be read or to be written and its size.

Based on these information, the call to do_param_partition_operation() in init_cc_flag_value() reads 64 bytes

from the param partition starting at the offset (end - 2048) and stores the bytes read into input;

Let's take a look at the data located at this offset. Dumping the param partition on a Samsung Galaxy S5 gives us the following results:

$ adb shell

shell@klte:/ $ su

root@klte:/data/local/tmp # dd if=/dev/block/param of=/sdcard/param.raw bs=4096

$ adb pull /sdcard/param.raw

$ hexdump -C param.raw

00000000 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 |................|

00000010 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00000020 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

*

00900000 44 4c 4f 57 04 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 |DLOW............|

00900010 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00900020 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

*

009ff400 04 47 39 30 30 46 58 58 55 31 42 4f 42 37 00 00 |.G900FXXU1BOB7..|

009ff410 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

*

009ff800 66 9a 46 f2 fe 58 d0 b7 b3 dc ad 51 c6 00 6a be |f.F..X.....Q..j.|

009ff810 c7 3b 41 b3 65 81 80 3c 70 44 55 2f 1c cb a0 b5 |.;A.e..<pDU/....|

009ff820 f9 56 18 9e 06 d3 13 8e 7d b3 2b 75 4c b4 c5 13 |.V......}.+uL...|

009ff830 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

*

009ffc00 bb 2d e1 bf bb 1e 8b 10 d8 e7 49 0b ca 42 4d 7b |.-........I..BM{|

009ffc10 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

*

00a00000

The param partition has a size of 0x00A00000 and we want to read the last 2048 bytes, which means we will start reading at hex(0x00a00000 - 2048) => 0x9ff800. Looking at the hexdump output, this buffer of 64 bytes is not human readable and looks like random bytes. It is probably encrypted.

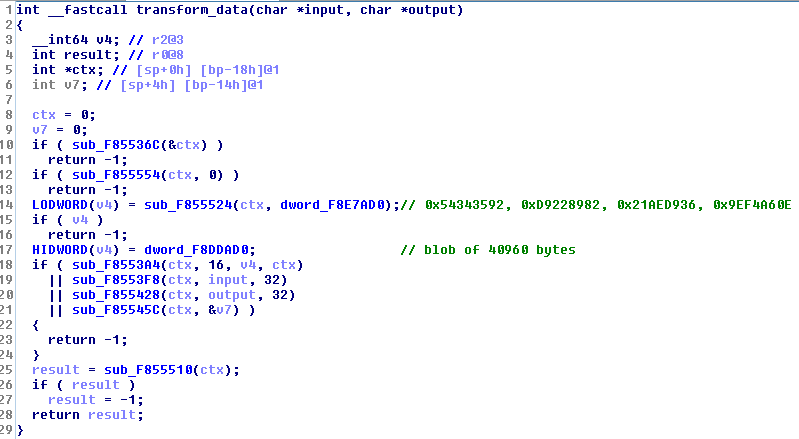

Let's try to understand how these data are used when the function renamed to transform_data is called:

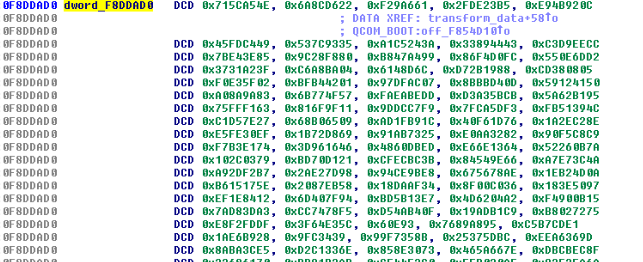

Multiple functions are called inside transform_data and it seems to initialize properties of an object that has been renamed ctx (for context). The signature of these functions make us think of cryptography primitives: we have a buffer of 16 bytes at dword_F8E7AD0 (maybe an IV?), a big "table" of 40960 bytes (certainly multiple smaller tables) at dword_F8DDAD0 and power of 2 constants (16/32).

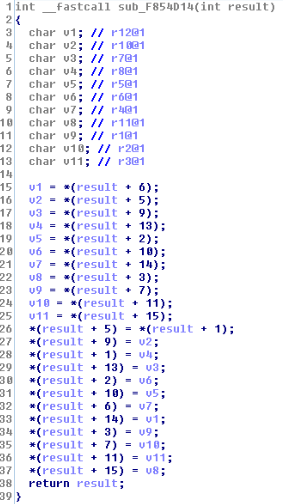

One of the inner function called by transform_data is a substitution on a 16 bytes array, which reminds invShiftRows operation in AES:

It seems that we are indeed in presence of cryptography, probably AES related. It looks like a whitebox cryptography implementation as we only have tables but no hardcoded key.

Instead of reverse engineering these functions, which can be time consuming without symbols, let's try to search for binaries related to them:

$ grep -Rn NOCC .

system/lib/libSecurityManagerNative.so

YAY! A result! And the exported functions look promising:

[...]

getCCModeFlag 0x00035A8

getSBFlag 0x0002D6C

setCCModeFlag 000030D0

[...]

WAES_Create_Cipher 0x0004B1C

WAES_Decrypt 0x0004C0C

WAES_Encrypt 0x0004BAC

WAES_Free_Cipher 0x0004C68

WAES_Set_Initial_Vector 0x0004C78

WAES_Set_T_Box 0x0004B44

[...]

Pretty interesting, isn't it ? We have functions to get/set CC flag, and many functions prefixed by WAES (for Whitebox AES ?) :)

To sum up, if we put specific data at a specific location in the param partition, then we can prevent aboot to switch the download mode. This data is encrypted by something that seems to be a whitebox AES implementation. This becomes more interesting :)

One may think that forging AES encrypted data without having the key seems to be problematic, but it's not. Even if I'm not a crypto guy and I don't break the whitebox AES implementation (maybe in a next blog post?), I can still use the whitebox as an oracle and ask it to encrypt or decrypt data for me without having to know the key.

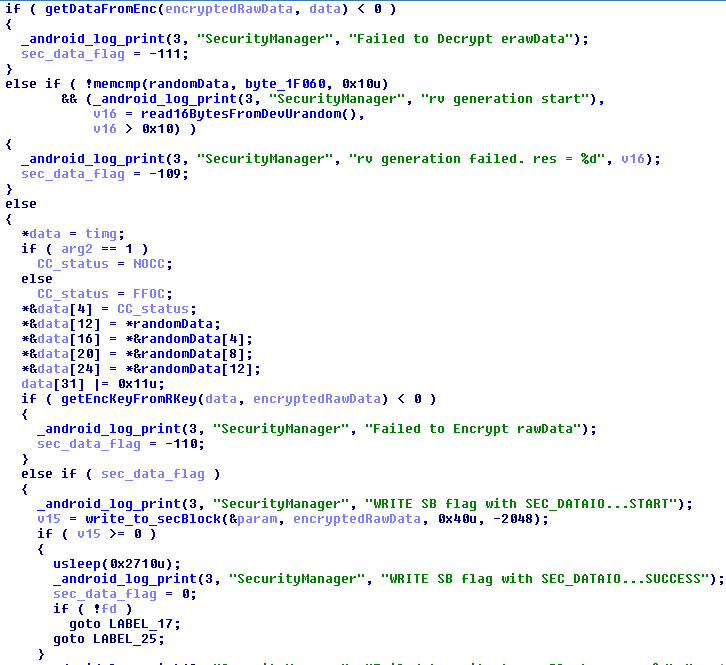

Indeed, we can invoke the code inside libSecurityManagerNative.so with dlsym()/dlopen(). The library contains a function named

setSBFlag() which will write NOCC or FFOC based on the value (1 or 0) of its 2nd argument:

Let's build a simple wrapper around this library:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <dlfcn.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

if(argc < 2){

printf("Usage: %s <0/1> (0: unlock, 1: lock)\n", argv[0]);

return 1;

}

void *lib = dlopen("/system/lib/libSecurityManagerNative.so", RTLD_LAZY);

printf("lib = %p\n", lib);

if(lib == NULL){

printf("dlerror: %s\n",dlerror());

return 1;

}

//setSBFlag(int arg1, int arg2)

int (*setSBFlag)(int arg1, int arg2);

setSBFlag = dlsym(lib, "setSBFlag");

printf("setSBFlag = %p\n", setSBFlag);

if(SBFlag){

printf("Unlocking the download mode!\n");

(*setSBFlag)(0, 0);

}else{

printf("Locking the download mode!\n");

(*setSBFlag)(1, 0);

}

return 0;

}

Now, we only have to push this wrapper in /data/local/tmp and run it as root:

$ adb push change_lock_status /data/local/tmp

$ adb shell

shell@klte:/ $ su

root@klte:/data/local/tmp # ./change_lock_status 1

$ adb reboot download

And finally here is the result:

Custom recovery and adbd

This is great, your download mode is locked! Now, what if you soft-brick your device for a random reason and you need to reflash it ? You can't access download mode anymore, which is a bit problematic.

To prevent such access loss and to allow easy switching between locked and unlocked state, I decided to implement a new command inside the adbd daemon and to put the modified adbd in the recovery of my smartphone. This way, each time I need to unlock the download mode, I only have to boot in recovery, enter the good password through the custom adb command, and then reboot in download mode.

Note: to implement this quick and dirty PoC, I used a Samsung Galaxy S5 (SM-G900F) test device running Android 5.0 (LRX21T.G900FXXU1BNL9)

Because we need to allow modification of param partition, our custom adbd binary has to be executed as root. To avoid bypass or security issues, we need to reduce the attack surface and we must not to expose adbd functionalities like adb shell or jdwp. I have chosen to implement a new service (command) in minadbd instead reusing of adbd. Minadbd is a light version of adbd, used generally to expose only the adb sideloading feature of a stock recovery.

These are my modifications of minadbd's source code from AOSP:

- We need to modify the Android.mk of minadbd to build a ELF static binary executable instead of the default libminadbd. You can append these lines at the end of the default minadbd's Android.mk file:

# minadbd binary

# =========================================================

include $(CLEAR_VARS)

LOCAL_SRC_FILES := \

adb.c \

fdevent.c \

fuse_adb_provider.c \

transport.c \

transport_usb.c \

sockets.c \

services.c \

usb_linux_client.c \

utils.c

LOCAL_CFLAGS := -O2 -g -DADB_HOST=0 -Wall -Wno-unused-parameter

LOCAL_CFLAGS += -D_XOPEN_SOURCE -D_GNU_SOURCE

LOCAL_C_INCLUDES += bootable/recovery

LOCAL_MODULE := minadbd

LOCAL_FORCE_STATIC_EXECUTABLE := true

LOCAL_STATIC_LIBRARIES := libfusesideload libcutils libc libmincrypt

include $(BUILD_EXECUTABLE)

- Then, we need to register two new "services" by adding them in the service_to_fd function:

int service_to_fd(const char *name)

{

int ret = -1;

if(!strncmp(name, "samsung_unlock:", 15)) {

ret = create_service_thread(samsung_unlock, (void*)(name + 15));

}else if(!strncmp(name, "exit", 5)) {

exit(0);

}

return ret;

}

samsung_unlock service is used to change the lock status for the download mode, and exit service to kill our minadbd if we want to be able to use adbd for sideloading. Other services have been removed from the service_to_fd() function.

- Now, we can implement our new service:

static void samsung_unlock(int fd, void *cookie)

{

if(strncmp((char *)cookie, "super_s3cr3t_p4ssw0rd!", 22) == 0) {

adb_write(fd, "OK4Y", 4);

system("ln -s /dev/block/mmcblk0p11 /dev/block/param");

system("rm /dev/random && ln -s /dev/urandom /dev/random");

system("change_lock_status && reboot download");

}else{

adb_write(fd, "F4IL", 4);

}

adb_close(fd);

}

When you want to change the status of the download mode, you only have to send samsung_unlock:super_s3cr3t_p4ssw0rd! through adb. The samsung_unlock() function will create two symbolic links and run our binary called change_lock_status.

The change_lock_status binary use libSecurityNativeManager.so through dlopen()/dlsym() to modify the param partition. As it tries to open /dev/block/param which doesn't exist in the stock recovery, we need to recreate the correct symlink. We also need to remove /dev/random and replace it with /dev/urandom because the libSecurityNativeManager.so tries to read from it and it hangs since there is not enough entropy.

Please note that this code snippet is only a sample of what can be done, it is not recommended to use it on your smartphone as it doesn't implement any protection like anti bruteforce. It's just a PoC.

- Finally, we need to add a main function to our minadbd binary:

--- a/minadbd/adb.c

+++ b/minadbd/adb.c

@@ -400,3 +400,9 @@ int adb_main()

return 0;

}

+

+int main(int argc, char **argv)

+{

+ D("Handling main()\n");

+ return adb_main();

+}

Let's build it:

$ cd ~/aosp/

$ source build/envsetup.sh

$ lunch

$ make minadbd

$ file out/target/product/generic/system/bin/minadbd

out/target/product/generic/system/bin/minadbd: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, ARM, EABI5 version 1 (SYSV), statically linked, stripped

YAY! Now we need to modify the stock recovery to add our custom minadbd binary:

- First we need to extract the stock recovery from our ROM:

$ tar xvf G900FXXU1BNL9_G900FOXX1BNL3_G900FXXU1BNL9_HOME.tar.md5 recovery.img

$ mkboot recovery.img /tmp/out/

Unpack & decompress recovery.img to /tmp/out

kernel : kernel

ramdisk : ramdisk

page size : 2048

kernel size : 8336160

ramdisk size : 2563133

dtb size : 1843200

base : 0x00000000

kernel offset : 0x00008000

ramdisk offset : 0x02000000

tags offset : 0x01e00000

dtb img : dt.img

cmd line : console=null androidboot.hardware=qcom user_debug=23 msm_rtb.filter=0x37 ehci-hcd.park=3

ramdisk is gzip format.

Unpack completed.

To allow easy unpack/repack of recovery.img, i used mkboot wrapper which can be found on github .

- Now we need to add our

minadbd, renamed assamsung_unlockbelow, as a service and start it at boot:

$ cp out/target/product/generic/system/bin/minadbd /tmp/out/ramdisk/sbin/samsung_unlock

$ nano /tmp/out/ramdisk/init.rc

[...]

service samsung_unlock /sbin/samsung_unlock --root_seclabel=u:r:su:s0

disabled

user root

group root

oneshot

[...]

on property:ge0n0sis.samsung_unlock=1

write /sys/class/android_usb/android0/enable 1

start samsung_unlock

[...]

$ nano /tmp/out/ramdisk/default.prop

[...]

ge0n0sis.samsung_unlock=1

- We also need to add

change_lock_statusbinary in the recovery. It's a dynamically linked ELF binary (because it usedlopen()/dlsym), thus we need to also put the linker binary and the dependencies in/vendor/lib(libSecurityNativeManager.soand it's own dependencies):

$ export RAMDISK=/tmp/out/ramdisk

$ cp /tmp/change_lock_status $RAMDISK/sbin/

$ cd ~/aosp/

$ make linker

$ file out/target/product/generic/system/bin/linker

out/target/product/generic/system/bin/linker: ELF 32-bit LSB shared object, ARM, EABI5 version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /system/bin/linker, not stripped

$ cp out/target/product/generic/system/bin/linker $RAMDISK/sbin/

$ sed -i "s|/system/bin/linker\x0|/sbin/linker\x0\x0\x0\x0\x0\x0\x0|g" $RAMDISK/sbin/change_lock_status

$ sed -i "s|/system/bin/linker\x0|/sbin/linker\x0\x0\x0\x0\x0\x0\x0|g" $RAMDISK/sbin/linker

$ mkdir -p $RAMDISK/vendor/lib

$ cp /tmp/libSecurityNativeManager.so $RAMDISK/vendor/lib

$ arm-linux-gnueabi-objdump -x $RAMDISK/sbin/change_lock_status |grep NEEDED

NEEDED libdl.so

NEEDED libstdc++.so

NEEDED libm.so

NEEDED libc.so

$ arm-linux-gnueabi-objdump -x $RAMDISK/vendor/lib/libSecurityManagerNative.so |grep NEEDED

NEEDED libcrypto.so

NEEDED libskmm.so

NEEDED liblog.so

NEEDED libstdc++.so

NEEDED libm.so

NEEDED libc.so

NEEDED libdl.so

$ adb pull /system/lib /tmp/lib

$ for i in libc.so libcrypto.so libdl.so liblog.so libm.so libskmm.so libstdc++.so;

do

cp /tmp/lib/$i $RAMDISK/vendor/lib;

done

- Our custom recovery is complete. We rebuild it, package it as a .tar.md5 file and flash it with ODIN:

$ mkboot /tmp/out/ /tmp/recovery.img

$ tar -H ustar -c recovery.img > recovery.tar

$ md5sum -t recovery.tar >> recovery.tar

$ mv recovery.tar recovery.tar.md5

Once flashed, we can reboot the smartphone in recovery mode and check if an adb device is detected:

$ adb device

List of devices attached

1e45xxxx **host**

Everything seems to be fine, but we still need to send our custom "samsung_unlock" command through adb. To do so, we will use a simple python client instead of modifying adb sources to build a new client supporting our command.

To communicate with an android USB device through adb, we only need to connect on 127.0.0.1:5037 on which adb server is listening and send "host:transport-usb" command to talk to the USB device. Once done, you can send your own adb services.

Below is an example of adb client source code to use the samsung_unlock service:

import sys

import socket

import argparse

def adb_send(s, data):

s.send("%04x%s" % (len(data), data))

def adb_recv(s, size):

return s.recv(size)

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser()

parser.add_argument("-p", "--password", dest="unlock_password")

parser.add_argument("-x", "--exit", dest="exit", action="store_true")

args = parser.parse_args()

s=socket.socket(socket.AF_INET,socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.connect(('127.0.0.1',5037))

adb_send(s, "host:transport-usb")

print adb_recv(s, 4)

if args.exit:

adb_send(s, "exit")

elif args.unlock_password:

adb_send(s, "unlock_download:"+sys.argv[1])

print adb_recv(s, 4)

print adb_recv(s, 4)

else:

print "nothing to do ..."

Conclusion

This article shows how reverse engineering of proprietary parts of Android can sometimes help to discover security features not enabled by default or not available to an end user. Based on this link, it seems that this feature can be enabled via a MDM interface. It's too bad that Samsung doesn't provide a simple way for its end users to manage the download mode access :(.

The present article was written while the author was affiliated with Quarkslab (www.quarkslab.com). The employer's authorization for publication does not constitute an endorsement of its content and the author remains solely responsible for it.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus